A Quick Look at DF I/O (basic ETL w/JSON over http to CSV and Parquet on MinIO) in Dask

Now that we’ve got Dask installed, it’s time to try some simple data preparation and extract, transform, load(ETL). While ETL is often not the most exciting thing, getting data is the first step of most adventures. Data tools don’t exist in a vacuum; the data normally comes from somewhere else, and the data or models we make need to be useable with other tools. Because of this, the formats and systems that a tool can interact with can make a difference between it being a fit or needing to keep looking. To simplify your life with I/O, you should make sure your notebook (or client) runs inside the same cluster as the workers.

For now, we’ll start by taking all of the GitHub activity from gharchive and re-partitioning it in a way that will allow us to try and train models on a per-organization and per-repo basis.

File Systems (e.g., Data Stores, Sinks, and well File Systems)

Often, the need to scale our Python programs comes at least in part from larger input sizes. When we use distributed systems (like Kubernetes), the data must be accessible to all workers. For this reason, we end up needing to get our data over the network. This does not have to be what one would traditionally think of as a network file system (like, say, NFS or AFS); it can include things such as HTTP, S3, HDFS, etc. All of these protocols expose some common file-like access.

Dask’s file access layer uses FSSPEC, from the intake project, to access the different file systems. Since FSSPEC supports such a range of file systems, it does not install the requirements for every supported file system. You can see what file systems are supported, and which ones need additional packages by running:

from fsspec.registry import known_implementations

known_implementationsIn my case the known implementations returns:

{'file': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.local.LocalFileSystem'},

'memory': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.memory.MemoryFileSystem'},

'dropbox': {'class': 'dropboxdrivefs.DropboxDriveFileSystem',

'err': 'DropboxFileSystem requires "dropboxdrivefs","requests" and "dropbox" to be installed'},

'http': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.http.HTTPFileSystem',

'err': 'HTTPFileSystem requires "requests" and "aiohttp" to be installed'},

'https': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.http.HTTPFileSystem',

'err': 'HTTPFileSystem requires "requests" and "aiohttp" to be installed'},

'zip': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.zip.ZipFileSystem'},

'gcs': {'class': 'gcsfs.GCSFileSystem',

'err': 'Please install gcsfs to access Google Storage'},

'gs': {'class': 'gcsfs.GCSFileSystem',

'err': 'Please install gcsfs to access Google Storage'},

'gdrive': {'class': 'gdrivefs.GoogleDriveFileSystem',

'err': 'Please install gdrivefs for access to Google Drive'},

'sftp': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.sftp.SFTPFileSystem',

'err': 'SFTPFileSystem requires "paramiko" to be installed'},

'ssh': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.sftp.SFTPFileSystem',

'err': 'SFTPFileSystem requires "paramiko" to be installed'},

'ftp': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.ftp.FTPFileSystem'},

'hdfs': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.hdfs.PyArrowHDFS',

'err': 'pyarrow and local java libraries required for HDFS'},

'webhdfs': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.webhdfs.WebHDFS',

'err': 'webHDFS access requires "requests" to be installed'},

's3': {'class': 's3fs.S3FileSystem', 'err': 'Install s3fs to access S3'},

'adl': {'class': 'adlfs.AzureDatalakeFileSystem',

'err': 'Install adlfs to access Azure Datalake Gen1'},

'abfs': {'class': 'adlfs.AzureBlobFileSystem',

'err': 'Install adlfs to access Azure Datalake Gen2 and Azure Blob Storage'},

'az': {'class': 'adlfs.AzureBlobFileSystem',

'err': 'Install adlfs to access Azure Datalake Gen2 and Azure Blob Storage'},

'cached': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.cached.CachingFileSystem'},

'blockcache': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.cached.CachingFileSystem'},

'filecache': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.cached.WholeFileCacheFileSystem'},

'simplecache': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.cached.SimpleCacheFileSystem'},

'dask': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.dask.DaskWorkerFileSystem',

'err': 'Install dask distributed to access worker file system'},

'github': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.github.GithubFileSystem',

'err': 'Install the requests package to use the github FS'},

'git': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.git.GitFileSystem',

'err': 'Install pygit2 to browse local git repos'},

'smb': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.smb.SMBFileSystem',

'err': 'SMB requires "smbprotocol" or "smbprotocol[kerberos]" installed'},

'jupyter': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.jupyter.JupyterFileSystem',

'err': 'Jupyter FS requires requests to be installed'},

'jlab': {'class': 'fsspec.implementations.jupyter.JupyterFileSystem',

'err': 'Jupyter FS requires requests to be installed'}}If you don’t see your file system supported, there are a few options ranging from writing a new spec for FSSPEC, to using a FUSE filesystem layer, or copying the data to a support file system.

Since I’m focused on experimentation, I decided to install all of the extra packages from https://github.com/intake/filesystem_spec/blob/master/setup.py as part of my Dockerfile in [ex_install_all_fs]. If we just wanted to support our example (reading from http and writing to S3 compatible FS) we could simplify that to [ex_install_just_s3_http].

pip install fsspec[s3] aiohttpOften distributed file systems require some level of configuration, although sometimes this configuration is "hidden" from the end user so it is not always as visible. With Dask, the configuration needs to be specified along with each reading/writing operation which makes the configuration more visible.

|

Note

|

In Hadoop based systems, configuration is often read from a combination of environment variables and mystery XML files, which, when working can feel like magic — but keep in mind, the most difficult configuration to debug is the configuration you can not find. |

Since we’re pulling our data over public http, we don’t need special configuration for that. However, for our write side, I’m using minio (an S3-compatible file system) which needs configuration. The endpoint_url is the service name from helm ls -n minio plus [namespace].svc.cluster.local. The key and secret are specified during the install (which we did in the previous post).

minio_storage_options = {

"key": "YOURACCESSKEY",

"secret": "YOURSECRETKEY",

"client_kwargs": {

"endpoint_url": "http://minio-1602984784.minio.svc.cluster.local:9000",

"region_name": 'us-east-1'

},

"config_kwargs": {"s3": {"signature_version": 's3v4'}},

}We’ll use these storage options in the next section when writing data to our MinIO server.

|

Warning

|

The first time I did this, I was unable to figure out what was going on for a few hours because I had "anon": "false", and the false string was automatically converted to the true boolean value. |

Sometimes data can also come from or be written to things that are even less like file systems than the web, such as databases. In Dask, these are represented in a way closer to how file formats are represented, which is what we are going to explore next.

(File) Formats

Dask has built in support for a variety of formats on top of the different file systems. Both the Bag and DataFrame APIs have their own IO functions (bag IO & dataframe IO).

In our case, the input format we’ve got is JSON and the target output format is Parquet. Dask DataFrame’s IO library supports both of those formats so we’ll use the DataFrame API. We could also do this with the Bag API.

Reading

To load the data we need to specify the files we want to load. On file systems that support listing (like S3, HDFS, local, etc.), we can use wild cards, but when using a file system without listing support we need to create a list of all of the files.

gh_archive_files=[]

while current_date < datetime.datetime.now() - datetime.timedelta(days=1):

current_date = current_date + datetime.timedelta(hours=1)

datestring = f'{current_date.year}-{current_date.month:02}-{current_date.day:02}-{current_date.hour}'

gh_url = f'http://data.githubarchive.org/{datestring}.json.gz'

gh_archive_files.append(gh_url)When I have a number of different inputs, I like to start with loading just the first file to explore the schema.

df = dd.read_json(gh_archive_files, compression='gzip')

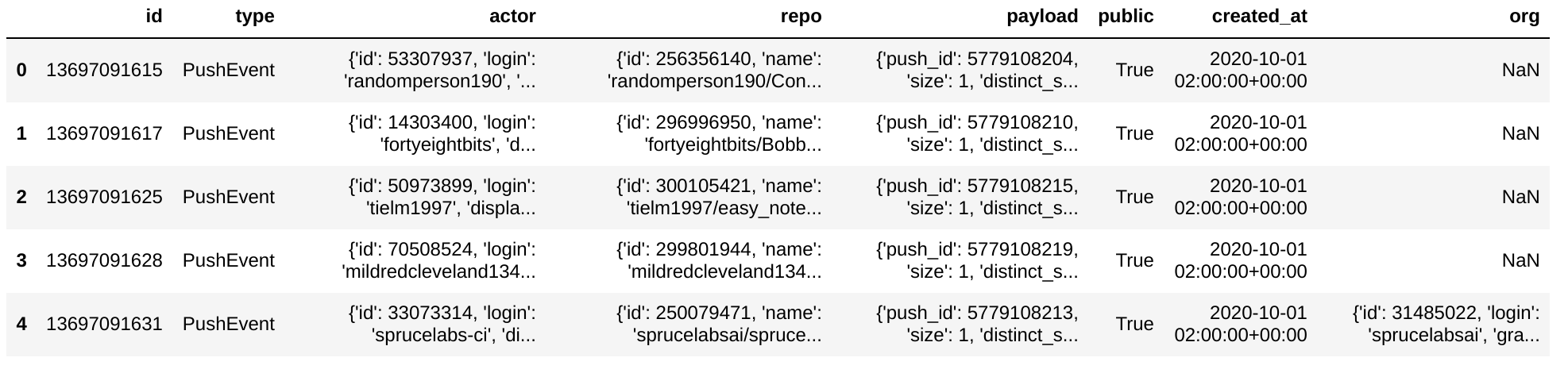

df.columnsAfter loading our initial input, calling "head" on the distributed DataFrame lets us see what’s going on.

df.head()Note the result of doing this (in IPython/Jupyter) is displayed using the normal pandas display logic, resulting in a nice image [dfheadimg].

If you’ve called df.head in Spark, you’ll note this is a much nicer default view. That being said the data needs a bit of cleaning up.

Some Quick Tidying Up

As we can see, there is nested JSON data in the DataFrame. I would like to partition on the project name so that, later, we can play around with data per-project without having to load everything (although I don’t think there is any automated filter push down). However, we can’t partition using a column that is a nested data structure, so we need to extract the project name.

def clean_record(record):

r = {

"repo": record[cols.get_loc("repo")],

"repo_name": record[cols.get_loc("repo")]["name"],

"type": record[cols.get_loc("type")],

"id": record[cols.get_loc("id")],

"created_at": record[cols.get_loc("created_at")],

"payload": record[cols.get_loc("payload")]}

return r

cleaned_up_bag = data_bag.map(clean_record)

res = cleaned_up_bag.to_dataframe()Writes

The write side looks very similar to the read side, but we’re going to use the minio_storage_options object we created earlier.

res.to_parquet("s3://dask-test/boop-test-partioned",

partition_on=["type", "repo_name"], # Based on " there will be no global groupby." I think this is the value we want.

compression="gzip",

storage_options=minio_storage_options, engine="pyarrow")Not all of the Dask formats support partitioned writes. When a format does not support partition_on or other partioned writes, Dask will need to either all of the data back to either a single executor or the client Python process. This can cause failures with large datasets.

Compression

Data is often stored in compressed formats, and the same library used to abstract file system access in Dask also abstracts compression. Some compression algorithms support random reads, but many do not. For people coming from the Hadoop ecosystem this can be thought of as the impact on "splitable."

Just because the underlying compression algorithm may support random reads does not mean that the FSSPEC wrapper will. Unfortunately, there is no current, easy way to check what a compression format supports besides testing it out or reading the source code.

|

Warning

|

Dask does not support "streaming" non-random access input formats. This means that the data inside a file must be able to fit entirely in memory. |

Conclusion

Dask I/O integrates pretty well into much of the existing "big data" ecosystem, although the methods of specifying configuration are a little bit different. Some nested data structures can be difficult to represent in certain formats with Dask, although as the Python libraries for these formats continue to improve so will Dask’s support.